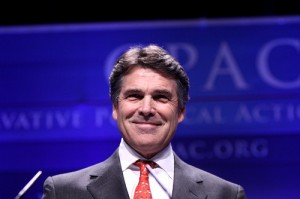

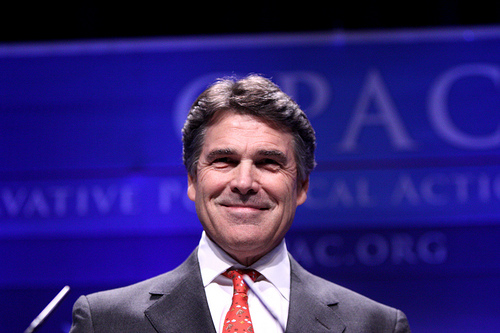

Why Iowa Evangelicals Haven’t Flocked To Rick Perry

On a drizzly, gray November day, the First Federated Church in Des Moines looked particularly formidable. The mega-church is a gigantic brick building, a converted high school that dominates the block. Its lack of aesthetic appeal didn’t deter the crowds. By the time approximately 3,000 people had filed in and taken their seats in the pews, the anticipation was palpable. The politics soon began.

Everyone was there for the “Family Forum,” a debate between GOP presidential candidates vying to win the critical Iowa caucuses on Jan. 3. But this debate would be less about issues than about religious and moral beliefs, and the candidates’ personal stories of faith. On the sanctuary stage was a long table with a cornucopia of pumpkins and vines—like a Last Supper table if the apostles had gone to Hobby Lobby. In the background hung pale yellow banners, completing the autumnal effect. Outside were signs advertising the event’s moderator, Frank Luntz, a Republican pollster who’s developed an audience among the Fox News-watching set. Of the Republican candidates, only Jon Huntsman and Mitt Romney—the two Mormons in the field—weren’t making appearances. The rest were competing for the support and endorsement of the group organizing this spectacle: The Family Leader.

A powerhouse in right-wing Iowa politics, The Family Leader made national headlines earlier this year when the organization asked presidential candidates to sign its “marriage vow,” promising to define marriage as between a man and woman, and to support a marriage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Romney refused to sign. He objected to a section of the document that appeared to argue that slavery was preferable to the current number of unwed African-American mothers. The comparison didn’t invite positive press.

But the group’s muscle is hard to ignore. It helped unseat several Iowa Supreme Court judges after the court ruled a ban on gay marriage unconstitutional. One prominent political news site, The Hill, ranked an endorsement from the group’s leader, Bob Vander Plaats, among the most coveted in the country. The Family Leader was hosting the Family Forum to highlight issues most debates hadn’t bothered to drill down on: which candidate is most pro-life, most anti-gay rights, most Christian.

In case it wasn’t clear just what kind of politics The Family Leader endorses, videos before the forum offered further hints. In one video, ominous music played while a deep voice burst forth: “These precious things we hold dear are in dire jeopardy. Not everyone believes in democracy. They don’t believe in the will of the people. And most important, they don’t believe in you.”

The video went on to criticize Iowa lawmakers who hadn’t worked hard enough to end gay marriage after the Iowa Supreme Court ruled the state had to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples. In another video, Vander Plaats’ face popped on the screen to talk about the national debt. “Some of us turn on TV, and we see $14.3 trillion, and we ask, ‘How can we do this?”’ Vander Plaats exclaimed. “The reason we’re doing this with the national debt is ’cause the focus is on me, not on the next generation. We as people of faith are called to have a multi-generational focus. And that’s what we at The Family Leader are doing.” Between the videos, contemporary Christian music blared from the speakers.

After a prayer and some introductions, Vander Plaats appeared in the flesh to kick things off, seeming more Sunday school teacher than hardened political kingmaker. He explained to the crowd that “for people of faith to remove their voice from the public policy process is spiritual negligence.” He beamed as he introduced his wife and offered that “we don’t need you to be Republican or Democrat, but we need you to be biblical.” He soon sat down to make way for the big star: Luntz.

The roly-poly pollster stepped off the stage and stood inches from the closest pews. He knitted his eyebrows and said in a voice dripping with solemnity, “Today is one of the most important days in my life because I want it to be one of the most significant days in your life. … I want you to understand what’s in these people’s hearts. Not just the sound bites.” It was a tall order, but Luntz went on, asking the audience’s permission to forgo “bells and buzzers” and “gotcha questions.” He promised the audience “real conversations.” The applause was thunderous. A few minutes later, the candidates appeared on stage and took their seats at the long table, completing the Last Supper tableau. And at the center, in Jesus’ traditional spot, sat Rick Perry.

BACK IN AUGUST, Perry’s campaign staffers probably dreamed about such a forum with Iowa evangelicals. It would have seemed the perfect event for their candidate. The Texas governor entered the race with a roar, disrupting the Iowa straw poll with his announcement. Even before he officially announced his presidential bid, Rick Perry had a two-part message: He’d brought jobs to Texas, and he’d done it by the will of God. The message seemed to stick.

While the governor bounced from Fox News to New York fundraisers expounding on the so-called Texas Miracle, he was also making clear that he believed wholeheartedly in a different kind of miracle.

At the beginning of August, Perry hosted a giant prayer rally he called “The Response.” The event attracted tens of thousands of believers with an unapologetically Christian message that was particularly appealing to fringe elements of the evangelical community, especially Christian Zionists and members of the New Apostolic Reformation movement, who believe in modern-day prophets with supernatural abilities. The event was hardly without controversy. The Anti-Defamation League, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, and the Southern Poverty Law Center all criticized the governor’s explicitly Christian rally. Perry called the event “a call to prayer for a nation in crisis.” It was the largest gathering any GOP candidate (or in Perry’s case, soon-to-be candidate) had put on, and it was geared entirely toward Christians.

The political strategy behind The Response was easy to see. By some estimates, evangelical Christians make up more than half of GOP caucus-goers in Iowa. Gay marriage has dominated Republican politics in Iowa, a state with a huge population of conservative, rural communities. With his own rural roots and evangelical ties, Perry seemed a natural fit. It also made political sense for Perry to focus on Iowa. His hardline social conservatism and Texas swagger weren’t likely to play well in New Hampshire, the earliest primary state, but Iowa’s caucus would come first, and if Perry could win over Iowans, a loss in New Hampshire wouldn’t matter as much. If he could capture the evangelicals, Perry would be tough to beat in Iowa, and probably in South Carolina too—states that former preacher Mike Huckabee won in 2008. Those key early wins might boost Perry to the nomination.

At first, the strategy seemed to be working. A few days after entering the race, Perry stopped at the Hamburg Inn in Iowa City. Famous for its pie shakes, in which an entire piece of pie is blended into a milkshake, the family-owned restaurant has catered to candidates as far back as Richard Nixon. The restaurant hosts the “coffee bean caucus,” in which patrons place a coffee bean in their favorite candidate’s jar.

The restaurant was packed with supporters when Perry visited in August, said kitchen manager Jay Schworn. The candidate arrived with a security detail, unusual for small-town Iowa meet-and-greets, but Schworn said the event was a success. “I am not by any means a supporter of the Republican Party or Rick Perry, but I honestly thought … he seemed to have all the pieces in terms of being the good-looking guy,” Schworn said. “He was very charming. I thought he definitely had potential.”

That potential seems long gone now. Perry quickly rocketed to the top of most polls, but on the campaign trail, voters simply didn’t respond. Despite out-fundraising his competitors, Perry seems more a late-night talk-show joke than a serious candidate these days, thanks to a series of debate gaffes. The fall from grace has been particularly dramatic in Iowa, where Perry peaked in August, polling as high as 29 percent. Now he’s down to between 7 and 9 percent, trailing both Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul, who once seemed long shots. Gingrich is outperforming Perry even among evangelicals—an unexpected turnabout given the former House speaker’s history of adultery and divorce. Even Perry’s jar in the coffee bean caucus is embarrassingly low. One server at the Hamburg Inn estimated Perry had only 40 beans, compared with Paul’s 400. Obama’s jar holds well into the thousands.

Iowa is Perry’s last chance to regain his status as a contender for the nomination. If Perry polls a distant fourth or fifth in Iowa, his campaign is likely finished. And his hope for a good showing in Iowa now rests with evangelicals. With only a few weeks to go, the campaign has clearly made such voters its focus. In early December, Perry released a blatantly anti-gay TV ad, introducing himself as a Christian before saying, “You don’t need to be in the pew every Sunday to know that there’s something wrong in this country when gays can serve openly in the military, but our kids can’t openly celebrate Christmas or pray in school.” The ad created a firestorm.

Perry the Christian is only the most recent of Perry’s campaign personas. First there was Perry the Job Creator. After his early gaffes put him on the defensive, Perry unleashed his inner tough guy, going after Romney in debates and on the air. When that didn’t play well, and after more egregious missteps, Perry tried to portray himself as a lovable bumbler, about substance over style. Now he’s back to courting the evangelical voters who once supported him in droves. Winning them back may take a miracle.

[Photo By Gage Skidmore]