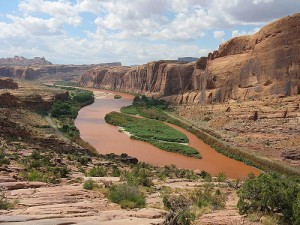

On the Colorado River, El Agua Es Vida

The recent Colorado River binational agreement between Mexico and the US has been deemed “historic” and “landmark”—adjectives well-deserved if one considers how the story of the Colorado River is a history representative of the “water wars” of the Western US. It is a fight over water rights, the lifeblood in the development of urban centers like Las Vegas and Los Angeles—but it is also an important story in how we will continue to deal with natural resource conservation we balance the competing needs and interests of people and nature.

The new agreement, an amendment to the 1944 water-sharing treaty, sets off a five-year pilot initiative, which if successful, will have a follow-up pact in 2019. It sets out new guidelines for how to share Colorado River water in good times and bad, also allowing Mexico to store its allocation in Lake Mead. In addition, a key piece of it is significant in what it does for ecosystem restoration. As Sandra Postel from National Geographic notes:

“The new agreement could demonstrate the potential to bring back crucial portions of the once-wondrous delta ecosystem, secure habitats for endangered species, and restore freshwater flows to the upper Gulf and its prized fisheries.”

It is important to restore an ecosystem for its own right, especially since past agreements mostly focused on the needs of people—but as the agreement moves forward, it is also important to point out what restoration of the ecosystem means in terms of the livelihood it provides to generations of Latino and Mexican communities along its path. As conservation issues and struggles continue in the Southwest, especially regarding water, it is important to have their voice in the dialogue.

Nuestro Rio is representative of cooperative efforts that highlight the value Latinos bring to conservation issues and the need for more of it—in this case with the Colorado River. The idea is to bring awareness of environmental issues to Latinos, but also to bring awareness of Latinos to conservation organizations, so that both sides understand the issues at stake, and appreciate the history that comes embedded. This is especially important given the deep Latino historical roots in the Southwest—roots sustained by how they managed water and other natural resources. As the Nuestro Rio website states:

“Latino heritage is now rooted in the northern Río Grande Watershed for 20 generations, and Latinos have developed a complex system of acequias, or irrigation canals, that have provided the basis for both their agriculture and their political organization…Today, the acequia culture of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado is a powerful bond that ties people to the land and nurtures the enduring sense of querencia, that powerful love of homeland that continues to prevail within Latino soul.”

I believe such an example also illustrates that many Latino communities care about natural resource conservation, but that a stronger connection and conservation ethic is forged for many Latinos when they engage with the ecosystem as they have for centuries—as part of a place called home. The Colorado River should be conserved for its own sake, but also because it is a cultural and historical asset, and a current livelihood provider. The river carved the Grand Canyon and fed a rich delta at the Gulf of California. But in our quest to solely use its water for development we threatened its ecosystem and existing communities dependent on it.

So as the binational agreement moves forward, it will be important to note how Latino communities are affected by and involved in the process—as with other conservation issues in places with deep Latino roots.

[Photo by stevendamron]